Steve Jobs did it in 1972. Bill Gates did it in 1974. More recently, so did Mark Zuckerberg and Jack Dorsey. I’m not talking about some illicit drug in vogue with the Silicon Valley elite (well, except for Jobs) – I’m talking about dropping out of college.

In recent years, dropping out to pursue a tech startup has become the new American Dream. With films like The Social Network, even mainstream Hollywood has bought into the mystique, painting romantic notions of bucking traditional education to change the world, all while making billions. Perhaps the most controversial manifestation of this trend is legendary entrepreneur and VC Peter Thiel’s Thiel Fellowship, formerly known as the “20 under 20”. This fellowship offers $100k each year to students under 20 on the condition that they drop out of school to pursue an idea. In the CNBC documentary trailer about the “20 under 20”, Sean Parker of Napster fame gives his take: “If your goal is to become an entrepreneur, it would seem that college has become a very bad place to do that” (watch the actual highlight here).

Well, I’m here to say *don’t* do it – do NOT drop out of school. Let’s start with some numbers.

The Numbers

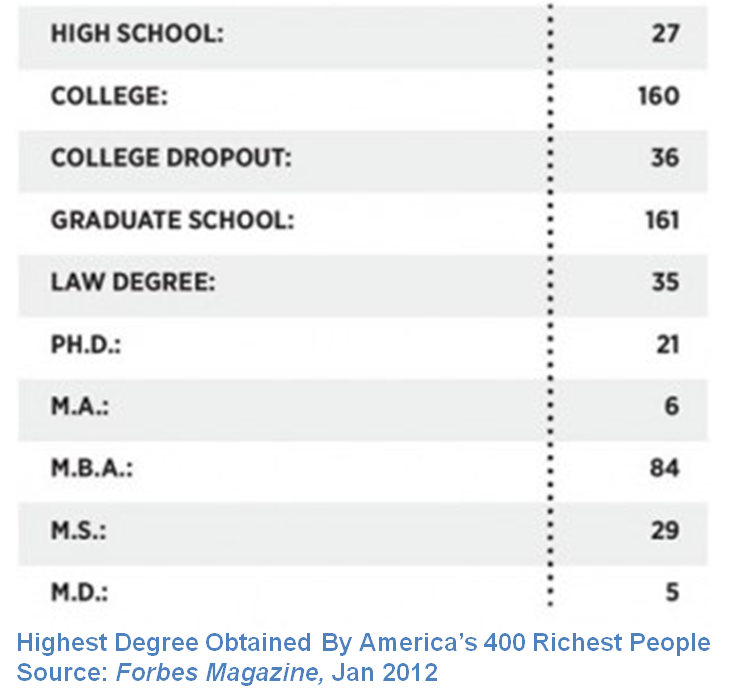

It’s pretty easy to come up with success stories, but what proportion of the whole do they actually make up? If we use wealth as a measure of success, Forbes’ January 2012 edition reveals that about 85% of America’s 400 Richest People (shown left) do, in fact, have a college degree. The top 400 is already an elite minority, and only an even smaller minority decided to forego traditional education.

It’s pretty easy to come up with success stories, but what proportion of the whole do they actually make up? If we use wealth as a measure of success, Forbes’ January 2012 edition reveals that about 85% of America’s 400 Richest People (shown left) do, in fact, have a college degree. The top 400 is already an elite minority, and only an even smaller minority decided to forego traditional education.

“But that’s the old guard,” you say. “We’re the new generation with new, innovative ways of doing things”. If you go younger, the trend is the same. I looked through this year’s Forbes 30 under 30 in the Tech category and an overwhelming 92.5% stuck to school. Even in a fuzzy category like Art & Style, 87% had undergraduate degrees or better. You can see my compiled results here.

But what if you don’t buy this numerical argument? Innovation is about going against the odds and taking risks, after all. I still argue, though, that we need a foundation to build from, and that foundation is school.

A Skills Foundation

From a practical perspective, a tech startup needs a sufficient pool of technical skills in software, hardware, the sciences, or even finance. This is especially true for the technical founder, who on top of writing code will need to architect designs, allocate resources, and otherwise set the tone for the entire engineering team as the company grows1. More often than not, this level of skill is fostered in some sort of formal education.

But why do you need college to develop these skills? There’s an old saying that sums up my view: “You don’t know what you don’t know”. To throw in some personal experience, I started out my programming career, like many others, by learning by doing. Through trial and error and the occasional book, I freelanced enough websites and apps that I almost considered myself a proficient developer. It wasn’t until I took courses in formal principles like design patterns, programming paradigms, or architecture that I realized how much I didn’t know. It wasn’t until I worked on team projects that I realized how many practical project management skills I didn’t have. At the time, I “didn’t know what I didn’t know”. In hindsight, embarking on my own startup before building a skills foundation would have been disastrous. As another example, James Proud, the first of the aforementioned “20 under 20” fellows to have sold his company, actually remarks in the New York Times that “he knows he is missing out on the deep computer science knowledge that he could learn in college”.

And even if you don’t actually have to go to college to learn the things I described above, a college degree provides a baseline measurement for both yourself and others to calibrate against.

Say you’re presiding over a loved one in critical condition after an accident. Suddenly a man pushes through the crowd and declares he is going to do emergency surgery. “Are you a doctor?” you ask. I’m pretty sure “No, I’m self-taught,” wouldn’t be your preferred reply.

That was a contrived example, but there are legitimate cases where a college degree serves as a proxy for qualifications: when you’re looking through resumes, when an investor is deciding whether to make a bet on your team. Like all proxies, it’s not perfect, but in a world with finite resources, it’s an unavoidable shortcut.

A Life Foundation

In addition to technical skills, college also teaches the life skills needed to succeed. Don’t worry – I’m not getting philosophical on you. As an engineer, I find unquantifiable “life skills” like “networking” a bit hokey. But as long as we’re talking about networking, where do you think most startups hire from? Or find their cofounders?

I met my co-founder Neil Joglekar in the dorms playing poker. After we were able to take each other’s money without wanting to kill each other (mostly), I knew we could get along as friends. And after working on class projects together, I knew we could function as a team. The same advice is reiterated on Hacker News time and time again: college is one of the best resources for starting your company and career. The population at large agrees – according to Forbes and Pew Research Center, 74% of respondents say college helped them grow intellectually, 69% say it helped them mature as a person, and 55% say it helped them prepare for a job or career.

But even if you believe the best school is the school of hard knocks, college as a skills proxy applies to life skills as well. For the outside observer, the fact that you completed college shows you can finish what you start.

For example, one of the biggest lessons I’ve learned as a founder is to persevere through the inevitable low points. Paul Graham calls this getting through the Trough of Sorrow. Seth Godin calls it getting past “The Dip” in the eponymous The Dip: A Little Book That Teaches You When to Quit. However you want to describe it, there will come a time that will test you and your team’s conviction. You’ll have to scrap your shiny new interface after usability testing reveals it’s not so shiny after all and start over from scratch. You’ll pour countless hours into creating single-use, throwaway presentations. And before you’ve actually performed these trials by fire, your past accomplishments are the only pseudo-guarantee your investors, co-founder, and team have that you won’t cut and run as soon as the next shiny thing comes along. For those of you deciding whether to drop out of school, your main accomplishment probably *is* school.

Stay in School

In closing, hopefully I’ve made the case for NOT dropping out of school to pursue a startup. I’d love to hear your perspective on the topic – please don’t hesitate to leave a comment below or contact me at yang.christian [at] gmail [dot] com. In the immortal words of Arthur Fonzarelli (am I showing my age?): “Staying in school… is cool.”

- If you’re a technical founder, check out John Allspaw’s great essay On Being A Senior Engineer ↩

I stayed in school. You know how a shareware author doesn’t need funding?

Computer networking? In 2005, I was getting hammered by the anti-malware hystaria. I felt uncomfortable, since I have an open system, so, I decided I would promise to never do networking and, thus, never have a malware problem, since it’s for writing your own programs. My original vision was a souped-up Commodore 64. It was used for bulletin boards with a modem, but networking wasn’t a big deal.

I have the chops for RS232 networking. I did a serial port driver. Computers don’t have serial ports, anymore. I removed it. I did plenty of RS232 networking code at Ticketmaster.

Ethernet? Probably many hardwares to support — creeping away from my original simple system model. I glanced at network protocols and found a list with a hundered protocols. Not sure what that was. I figured whatever protocol microsoft uses between its computers was not my business. I could make my own protocol. That’s what Ticketmaster did, even doing a propriatary VAX operating system.

I want to invent, not reverse engineer and implement standards with no opportunity for self expression. What could I bring to the table if I did a browser? You are not allowed to change html, unless you’re on a mission from God or something. Those standards companys do a bad job, by the way. They are guilds which try to keep jobs with-in the members. They are evil.

I’m not making a general purpose competing operating system, but an add-on stand alone that’s just for fun. If it’s not your main system, there is no point redoing all the things you can do on your main system. I’m not interested in Open Office? Just use your main operating system. I’m not interested in web browsing or multimedia. Just use your main system. Don’t need to support printers. Pretty-much just for users writing games and enjoying low level power, like playing with disk blocks if they like, or playing with the task scheduler or makinhg a file system or just browising and changing values for a few hours of fun.

With a C64 you used to be able to put live memory on the graphcis screen. It was neat. You could do animation with fonts. Cheap thrills.

I disagree completely. For most, the college years are a time of relative freedom and little risk. And, increasingly, colleges are becoming more understanding of students taking time off (for whatever reason) and readmission is no big issue. Given this backdrop, if you have an idea and the means to spend a year or more outside the college bubble to pursue it – go for it.

What’s the downside? If your company takes off, you become one of the degree-less success stories that you (correctly) highlight as being so rare. If things don’t work out, return to school and finish your degree. What have you lost? Some time and money, perhaps. But the experience of having been out there in the “real world,” working on something “real” and interacting with “real” people holds immense value.

You say that college “teaches the life skills needed to succeed.” And it does. But it can also be a very insular and limited learning environment. Someone with a bold, adventurous, entrepreneurial sprit will more often than not develop, grow and learn much faster, and better, out in the real world working on real projects. And, in fact, I would argue that one is also better positioned to get the most out of college having spent some time in the real world first.

Alternatively, you find value in the completed college degree as a metric by which outside observers can evaluate and judge you. Does that really matter to the entrepreneur, who by definition is operating quite independently, outside of existing rubrics? Whenever it does matter, people see that you’ve undertaken some tertiary study and that’s enough.

During 2012 I spent a year away from college, working on a startup I cofounded. It was an amazing experience: I made countless valuable connections, honed my sales skills, picked up a few new programming languages, learned just enough about financing, and so much more. Things didn’t work out, but the only casualty was some seed funding. I’m headed back to school to finish my degree, with many more tools in my belt and a few fledgling ideas that will be ready for me when I graduate.

Thank you for this thoughtful and well reasoned article. Though I have obvious admiration for Peter Tiel, I think his advice is downright horrendous for the vast majority of people considering delaying an education. GS points out that it’s not a big deal to take a year to pursue an exciting opportunity, and, were all startups confined to only 12 month lifespans, he’d be right on. I co-founded a company in 2008 during a hiatus from school. It took four years of successes, failures, and incredibly expensive learning experiences for the startup to run through it’s lifecycle. Given the assumption that global net opportunity will be roughly equal in four years (or greater than) it is today, there are very few startup dreams that are worth deferring one’s education.

Nice article, but can’t say I’m completely convinced. Just to make it short, I noticed you attended Stanford. In such cases college can be a great experience (including MIT, etc). But I happen to live in another country where college isn’t that great with no so great professors and is mostly seen as a waste of time. Why being forced to attend somewhere where you don’t feel you’re really learning but rather wasting your time? Being self-tought is possible and even holds more value than attending lectures. Hopefully ebooks + Coursera and others will help boost this.

It’s all about timing. If you can prove to yourself and the people who matter (i.e. people whose opinions you care about) that your concept works, then go for it. There’s no reason why you can’t bootstrap a business and continue in college for a while before making the choice. Heck, some of your best customers are likely to be your classmates.

I’m a little late to the game, but here are my thoughts. Your advice is sound, though I might put it a different way. Finish school if you take time off to try a startup. Because chances are very high, that your startup is gonna fail. I have worked for 4 startups and none of them made me a millionaire. They were all great experiences and I have no regrets.

CS/IT degrees do actually provide sound training for your profession. So if you go to that startup, live cheap, save some money, and have a plan B if things do not work out.

The numbers you’re citing are pretty badly misleading. Citing the percentage of drop outs vs grads in the Forbes 400 says basically nothing about the value of a college degree for massive wealth.

It doesn’t take into account that the fraction of dropouts who do it to start a company is probably tiny compared to the fraction who do it because of poor grades, difficult financial circumstances, etc. In fact, I would guess (without actually running the numbers, mind you), given the typical circumstances of a college dropout vs a college graduate, that having 36 / 400 is a really HIGH number. Same goes w/ the 30 under 30 analysis.

It’s a little ironic, because one of the main arguments for a liberal arts education is that it teaches critical thinking skills — ie, the ability to look at evidence and draw the right conclusion from it. This is pretty much a big Stats 101 fail right here.

Pingback: Advice from an Entreprenuer to Students: Don’t Drop Out of College |

Great post ! You know, it depends from your perspective and timing. There was a time where I felt my Masters was a total waste of time; however I have made some businesses, decisions and networking that I couldn’t have done without the MSc or College. I think , for most of the people, is better to finish college and have this Skills foundation you mention.. congrats

Pingback: When to Drop Out of School? — Not Only Luck

Pingback: The Cult of Startup Dropouts @FounderCode